Biodegradable plastic film for sustainable disposal

The post below was published in CIWM Circular Journal, p 64-67, Winter, 2024, circularonline.co.uk, summarising an ACA cafe in Aberdeen on 6th February 2024.

The future direction for single-use packaging was the topic on everyone’s mind at a recent Aberdeen Climate Action Café in Aberdeen. We caught up with three of the speakers and asked them to outline what needs to be done to accelerate the UK’s journey

towards plastics circularity

By: Bob Pringle, ACA, Phoebe Russell, Vegware, and Nicola Buckland, Sheffield University

Plastic pollution continues to be a huge problem and shows no sign of getting any better. Materials such as PET and HDPE are ‘necessary evils’ – solving some problems while creating others, because of their persistence in the environment. Plastic film is getting thinner and thinner, making it all but worthless to recycle – but without it, food doesn’t last as long and organic waste balloons. It’s a complicated problem that is not going to be fixed with a single simple answer.

We disagree with the view of the plastics industry, that recycling will produce a sustainable solution to the problem of plastic pollution. There must also be interventions by government, new materials developed, and behaviours changed if we are to turn a corner.

Recycling alone is insufficient because the plastics in bottles and containers have physical and chemical properties that conspire to make them difficult to simply melt down and use again.

First, they are made from different polymers, each with their own melting-point. Only those of a similar type will mix together homogeneously, which is why sorting at material recovery facilities (MRFs) is so important-and tricky.

Drinks bottles are mainly colourless, but shampoo and chemical containers come in many different colours, which requires a second step to sort. In the reprocessing processes, strong dyes must be added to the mix to mask these differing colours; the next time round, even stronger dyes are required.

MRFs in conurbations can justify these expensive separation systems, but in island and rural areas such investment is harder to justify, resulting in carbon-intensive transport of recyclable waste to cities.

Many single-use plastics support combustion, which means they will readily fuel a waste fire started by a lithium-ion battery, for example. This makes their storage and processing a safety risk that must be mitigated.

Given these barriers, we believe the UK’s current plastics recycling regime is not sufficient to move the country towards a truly circular, sustainable system. So what needs to be put in place to make this happen?

Start-of-pipe solutions

One way to make bottle recycling more viable would be to change from our current ‘end of pipe’ thinking, which allows manufacturers to produce any plastic or colour of product they want, to a ‘start of pipe’ solution, where bottle polymers and colours are restricted.

The government could legislate so that only four types and colours of plastic container are permitted for use as packaging:

- Clear PET (1) for drinks

- Natural milky white HDPE (2) for milk bottles

- White opaque HDPE (2) for shampoos and chemicals

- Polypropylene (5) for yoghurt-type containers.

Colour and information would appear on paper stuck to the bottles, with a suitable adhesive, which would wash off during recycling, for subsequent composting.

The government could also legislate for oil-based plastic films (aka soft plastics) to be replaced by truly compostable plastics, phasing them in over three years. These are usually made from plant-based materials (maize, seaweed, etc), and can be eaten by microorganisms, meaning they break down when in contact with soil.

In the past, there have been false claims that plastics are ‘degradable’ or ‘compostable’ when, in reality many such materials don’t decompose in the conditions found in garden composters. That situation is, thankfully, changing and consumers can now be more confident that any bio-plastic item with a ‘TUV Austria: Home’ logo should successfully compost within six months in a domestic garden composter.

Such truly compostable degradable plastics materials are used by Vegware to make its 500+ packaging products. For example, Bagasse (a by-product of the sugar-cane industry) can be moulded into various shapes, including burger boxes and clamshell containers. Paper and card from sustainable sources can also be used to make compostable products, all of which can be broken down by microorganism. Polylactic Acid (made from corn or sugarcane) is a bioplastic used in a wide range of products including cold cups, lids, and the lining of coffee cups. When compostable films are used to line paper coffee cups, it makes the whole item compostable.

Compostable food packaging avoids the problem of used food packaging, that’s not clean enough to recycle, ending up in residual waste instead. If such an item is heading for composting anyway, the packaging and food waste can be collected and disposed of together, either at a local in-vessel composting (IVC) facility or anaerobic digestion (AD) plant. This is the model that Vegware uses for its in-house waste collection service, called ‘Close the Loop’, which enables its customers to compost their used Vegware packaging.

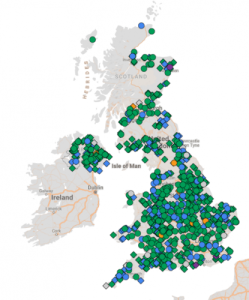

There are hundreds of ADs throughout the country, though fewer IVC plants. While many ADs are traditionally employed for sewage treatment and farm waste, the advantage of using them for municipal food waste and compostable packaging is that operators are paid a gate fee. AD plants produce biogas that can be connected into the gas grid or used to fuel lorries or generate electricity. The residual digestate can be spread on fields to fertilise crops.

These processes not only return nutrients to the soil, but also avoid the need for paper and plastics (provided they are degradable) to be sent abroad for treatment.

While many AD plants have front-end equipment to screen out plastic, it is still problematic to remove it all and stop the material getting to the digester. If oil-based plastics were phased out, however, shredded bioplastic packaging could also be suitable as feed stock.

A behavioural shift

There is one major problem with degradable plastics; they look and feel like conventional single-use plastics. That means people often find it difficult to identify compostable packaging as such. As a result, a lot of it gets put in the wrong bin – usually recycling or general waste.

Research by the Compostable Coalition UK – in collaboration with Vegware, Recorra, Hubbub and waste consultancy Eunomia – has shown that behavioural interventions such as having clear and distinctive labelling increases the amount of packaging that people place in the correct bin.

In one study, the team developed a behavioural intervention that aimed to increase the amount of compostable packaging put into compostables bins at three workplaces where compostable cups, salad boxes, and cutlery (supplied by Vegware) were available.

The researchers found that distinctive pink labels saying ‘put in the compostable bin’ helped to overcome confusion with conventional oil-based plastic items. Pink was chosen for its saliency and distinctiveness and because no UK packaging disposal labels are pink.

Hubbub designed the label which was also made from compostable materials) with input from OPRL, (On-Pack Recycling Labels).

The intervention was a success, significantly increasing the amount of compostables collected in all three workplaces and demonstrating that the compostable packaging industry could follow suit-producing a standard label that clearly states if products are degradable. Currently, there is no such UK standard.

Another crucial piece of the puzzle is a deposit return scheme (DRS), which we believe the UK must implement if it is to get to a circular system functioning properly.

While there is some concern that local authorities will lose revenue because of the reduced number of bottles and cans they will collect, research from the US in the 1990s shows that 95 per cent of bottles are returned when a deposit is required. The figure falls to just 45-50 per cent when a deposit isn’t needed.

Of course, there is also no reason why bottles have to be shredded or smashed; they can simply be used again.

All of the actions we have mentioned here – from the use of compostable materials to behaviour change and deposit return schemes – will take time to implement. But we must move forward with ideas such as these if the UK is to get serious about reducing its plastics waste and pollution. Only a truly circular, sustainable system will benefit society and the planet.