Household waste overview

Household waste overview

21/05/18

With an Energy from Waste (EFW) plant (incinerator) soon scheduled for construction in Altens industrial estate, Aberdeen, now is a good time to assess whether this investment is wise. Such large investments have a life of 25 years plus, so they must accommodate likely changes in waste collections over this period.

This section discusses 1) Future waste policy for Scotland’s household waste that considers recent developments, 2) A Strategy for plastic packaging, and 3) An Immediate waste policy for Aberdeen City Council.

1. Future waste policy for Scotland’s household waste

Recent developments

Five recent developments are likely to impact on household waste collection and treatment in the near to long term: –

- The realisation from the Blue Planet TV series that we cannot go on littering the planet with oil-based plastic packaging

- China’s refusal to continue taking our recycled waste paper and plastic for reprocessing

- The plateauing of Aberdeen’s recycling rates and the recognition that flimsy plastic packaging is unlikely ever to be recycled

- Food waste being still a major contaminant of residual waste

- Zero waste Scotland’s directive that no biodegradable waste should be landfilled post 2020

Progress with recycling since 1996

The phased UK government imposition of a landfill tax in 1996, has made the disposal of residual (general) waste ever more expensive. This has favoured the collection of recyclable wastes for processing as it escapes this tax, which was the government’s intention.

The low cost of labour in China meant that the cleaning and processing costs of recyclables in the past were low. This more than offset the cost of transport. China also provided a market for the recycled products, so demand for paper and plastics held up.

Now that China has shut its doors to this supply, the cost of cleaning and processing recyclables in the UK is bound to be higher. Possibly, other low wage countries will take over from China, but this is not a sustainable long-term solution. Surplus paper and plastics could be burnt, but the government stipulates that material collected for recycling should not be burnt, as this could reduce householders’ willingness to separate material for recycling in the home.

The plateauing of the recycling rate and the recognition that flimsy plastic packaging may not be worth reprocessing, is likely to deter entrepreneurs developing a UK reprocessing industry to take over from the Chinese.

The council has failed to encourage householders to keep food waste out of residual waste bins. This together with the Zero waste government’s directive that no food waste is to be landfilled after 2020, has led councils to consider burning food contaminated residual waste. While it makes no sense to use plastic and paper as a fuel to burn food, it does prevent biodegradable waste going to landfill.

What the government thought was a good idea to prevent greenhouse gas production from landfill has resulted in a move away from recycling and composting to simply burning residual waste to get rid of a problem.

What should the Scottish Government/local authority strategy be?

Rather than the government subsidising investment in UK reprocessing equipment, it is worthwhile taking a step back to reconsider the whole single use waste packaging production and recovery system. This would entail manufacturers and retailers taking real responsibility for what happens to packaging at the end of use. For this to happen packaging items would be clearly marked 1) Returnable / reuseable, 2) Recyclable, 3) Compostable or 4) Burnable. Vague terms like “May be recycled”, would not be allowed. The post use treatment would therefore be as below: –

- Returnable / Re-useable : – Drinks container bearing a deposit returned to supermarket by householder next time they shop → Back load to distribution centre → back load to supplier→ washing prior to refilling or sent to a reprocessor for shredding or melting

- Recyclable plastics: – Collected by council → kerbside segregated/MRF → separated → contaminants removed → baled → lorry to factory → contaminates removal → shredding → washing → drying → heating → pellet manufacture → melt → extrude into new product

- Compostable packaging: – Placed in kitchen caddy for composting or Anaerobic digestion (AD)

- Burnable: – Put burnable waste in residual waste wheelie bin→ Collected by council → Separated from other residuals → made into residue derived fuel bales → shipped to energy from waste (Efw) plant in UK or Europe → Burnt to produce energy

Assessment of above waste treatment options

In terms of simplicity, and the minimisation of labour and transport costs, options 1 and 3 win easily.

Returnable / Re-useable : –. A requirement for containers to bear a deposit is mandatory in eleven states in the US, which have introduced “bottle bills”. Not only has this measure massively improved return and recycling rates, to over 90% (compared to the UK’s 58% for plastic bottles in 2017) but it reduces litter composed of 40% drinks containers to 6% and provides income for poor people who collect discarded containers. Introducing bottle bills in the USA, however, involved a huge battle with drinks manufacturers. Companies in the UK have not had this imposed on them yet. Our councils presently bear the main cost of collecting and dealing with one-use containers following disposal, with manufacturers and retailers paying only a proportion via packaging recovery notes (PRNs). Profits have therefore been privatised and clean-up costs fall on us the public.

Compostable packaging: – Whatever manufacturer’s state on their packaging about material being “not currently recyclable” or “check local recycling”, flimsy plastic bags, cling film, polythene bags, crisp packets, clear polystyrene boxes, hardware packs with polystyrene display windows are unlikely ever to be recycled in practice.

Biodegradable packaging, including see-through film, is readily available either as paper bags or plastic films made from corn or potatoes and could be required by government to be used for all situations where packaging is unlikely to be reprocessed.

Recyclable : – This option would only be used for plastics and paper suitable for reprocessing, such as PET, HDPE and clean paper and cardboard. The greater the reuse of bottles, the less need for reprocessing.

Burnable: – While there will always need to be an option to burn certain items of household waste like shoes and items made from mixed materials, to avoid sending this material to landfill, it has numerous limitations. New UK regulation requires burnable waste to be separated after collection from residual waste and bans the burning of recyclables. This separation process, while sensible, adds an extra cost to the previous practice of burning unseparated municipal waste.

2. A Strategy for plastic packaging

A simple strategy can solve this environmental issue surrounding plastics in the environment, but needs the government to act. The strategy would state that:

- Oil based plastic bottles must all have deposits on them

- Other food and dry goods packaging exiting through the retailer door must be biodegradable

Survey data (Warmer Bulletin, 2002) exists to show that bottle recycling exceeds 90% if the bottles have deposits on them. Litter is reduced as any bottles lying around give scavengers an income.

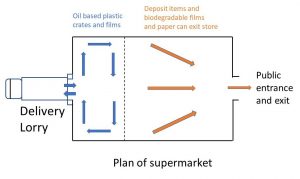

Retailers can use any oil- based plastics they like in their supply chain, so long as they return them for reuse or for recycling through their supply chain (See diagram). Much packaging already returns in the virtually empty lorries returning for the next delivery.

However, items for sale such as fruit and vegetable plastic containers, meat boxes, bakery containers, crisp packets, confectionery, all must be biodegradable. This will ensure that any litter created by these items rapidly breaks down in contact with the soil.

Surely we can burn oil based plastics?

Increasingly the waste management industry sees burning as the answer to difficult-to- recycle waste plastics, contaminated paper and cardboard. If all waste were collected, this would be one solution; but a proportion will always end up as litter. Therefore, potential wastes must be biodegradable. This does not rule out burning as a waste disposal option, but it will reduce litter.

Understanding oil-based plastics

Oil-based plastics are man-made polymers, numbered 1-7, with differing properties which suit different purposes. PET, No 1, is used for drinks bottles, HTPE, No 2, is used for shampoo bottles and so on. These polymers all have different melting points, so are largely incompatible when it comes to recycling and reprocessing. They must therefore be separated before being reprocessed. While bottles are worth recycling, the films which cover much of our fruit and prepared meats are not. They often have a label “not currently recycled”.

To you and I these films look like plain polythene (LDPE, No 4). Some are, but some are not. While all films hold water, they differ in the rate that they allow oxygen and carbon dioxide gases to pass through. This makes them suitable for use in modified atmosphere packaging, where fruit like strawberries, living organisms like us humans, create a high carbon dioxide (CO2) atmosphere within the pack. This reduces their rate of decay and so extends their shelf life. To achieve the correct permeability for the CO2 and oxygen, two or more laminates of different polymers may be used. This makes them almost impossible to recycle. In addition, their flimsy nature makes them more trouble to recycle than they are worth. So, “not ever likely to be recycled” should perhaps be on the label.

Strong dye needed to obtain a uniform colour. What happens when these bags are recycled?

The last aspect of oil-based plastic recycling is colour. Plastics must be separated into their different colours. Since these colours vary in shade, the final product must have a strong dye added to produce a standard product. The question is what to do with this plastic the next time round.

Plastics for preservation

Plastic packaging has two great advantages over paper. It prevents moisture loss, keeping fruit and vegetables firm and bakeries soft and fresh. It can also be made translucent, so customers can see the contents within the pack. Biodegradable plastics can do the same job. Work on biodegradable packaging for modified packaging is well developed. One complication is the aluminium film used to coat crisp packets, sweet wrappers and of course Tetra Pak. This is very effective in slowing vapour movement into the packet, greatly extending product shelf life. The aluminium is unlikely to be compatible with disposal by composting. This is an issue that needs development. As production of biodegradable packaging is a tiny fraction of oil-based plastics, it is more expensive. This in part may be due to the small scale of production at less than 0.2% of the plastic packaging market. Like wind generators and solar panels, costs should fall as output increases.

How plastic can impede food waste disposal

Broccoli for example is often wrapped in clingfilm to minimise moisture loss. While the clingfilm is good for increasing its shelf life, this makes it unsuitable for feeding to cattle should it turn yellow. The plastic can choke cattle, so the load has either to be landfilled, burnt or sent to a composting or anaerobic digestion plant with plastics separation equipment. Far better to supply the broccoli in a reusable plastic tray, encased in a large plastic bag, which is cut open once the vegetable is on display. The bag can then be returned to the supplier to deal with. Decayed vegetables can be decanted from the bags and fed to livestock.

London-Iona recycling test

When considering a recycling strategy, it is important to ask the questions “Can recycling be achieved as easily on the Island of Iona as in London?” If the answer is no, then we should consider other options. If we must rely on complex Materials Recycling Facilities (MRFs, pronounced Murfs), waste put in wheelie bins by householders in Iona have a long way to go to be recycled. In contrast wastes that can be composted can be treated locally either in local composting plant or in anaerobic digesters.

Recycling of oil-based plastics in a state of flux

Reprocessing plastics is a daunting task

As of this year (2018) the Chinese are refusing to keep taking the UKs plastic waste. Until now this has been the preferred route for dealing with waste plastics as their labour costs for processing the waste are so low. The government now has an opportunity to decide on a future strategy for plastic packaging, so Uk industry can invest in confidence in plastic recycling equipment. The alternative is to find new low wage countries like India, Bangladesh or the Philippines that will process our waste, with environmental standards that may leave much to be desired.

Resistance to changes

The introduction of deposits on plastics bottles is likely to be opposed by retailers and drinks manufacturers. We the public presently subsidise their business, as in 2018, they are only required to retrieve 51% of the plastic packaging they produce.

Retailers protest about the additional space in their premises required by deposit systems. This should be treated with scepticism. If 1000 bottles are sold per day and 1000 returned per day, what additional storage, other than a sorting area is required?

Companies manufacturing oil-based plastics may resist a move to biodegradable plastics and lobby government accordingly. However, government is increasingly aware of past campaigns by vested interests to “muddy the water”, so the industry would do well to be positive about an integrated strategy. With the scenario presented, there is plenty scope for oil-based plastics to be used within the food industry’s internal orbit.

Recent developments

The recent cases of microbeads in cleansing products, cotton buds and drinking straws, and tea bags, all confirm the logic of moving away from oil-based plastics. Micro-beads are to be made instead from coconuts, apricot seeds, walnuts, bamboo and rice, all biodegradable. The suggested solution to cotton buds is to replace the plastic sticks with paper ones, so both cotton bud and stick are biodegradable. The plastics straws are to be discontinued and ones made of biodegradable paper sold instead. The plastic in tea bags is to be removed.

Plastic packaging conventions

Disposable coffee cups will be biodegradable and deposited in compost bins after use. A latte tax or various inducements may in addition be introduced to get people to use reusable cups, thermos cups, etc. This will remove the waste coffee cup problem at source.

Retailers, including small stores and sweetie shops, would only sell oil-based plastic bottles with deposits on them. (Cans and glass bottles would have similar deposits). Packaging from supermarkets, convenience stores, corner stores, DIY stores would all be biodegradable, either paper of biodegradable plastics.

Food and material deliveries to retail outlets can use oil-based packaging, but it must be returned in the delivery trucks to suppliers for reuse, recycling or disposal.

Work will be required to bring biodegradable plastic packing to the level of extended shelf life that our present oil-based plastics have, but work on this is already in progress.

These new measures should be phased in over a period sufficient to ensure that the change-over does not cause confusion. Once the policy is decided, this policy should be maintained, so that commerce has a firm assurance that the measures will become law at firm dates decided by government.

This new approach must be carried out in concert with our trading partners be they the EU or further afield. We need consistency to be effective.

3. Future waste strategy for Aberdeen City Council

The UK government’s waste consultants, Eunomia, say that there will soon be too much waste-burning capacity in the UK. No, says the waste industry, it will be too little, we need more? Who are we to believe? Are large investments like our proposed EFW plant / Incinerator sensible; or for that matter, the recently completed Alten’s Materials Reclamation Facility (MRF, pronounced Murf).

Added council charges from new MRF

Firstly, the MRF. This is now built, and separates our waste, so it is “water under the bridge”. Or is there a lesson to be learned? A recent report from the Wales based government agency WRAP, (WRAP, 2016) suggests that the recent change to a co-mingled waste collection system is costing Aberdeen Council tax payers an extra £16.60 per household per annum compared to what we had before, the kerbside sort system.

The main reason the kerbside sort system used to be cheaper is that householders did the separation of the recyclables at no cost. The result from the Welsh study was the same for rural and urban communities of 60,000 households each.

Another report (ZWS, Nov. 2017), shows that the contamination rate increases from 10% to 19% when changing from kerbside sort to the co-mingled collection system we now have.

As far as I know, no similar studies have been done for Aberdeen. If it was, could we now please see them? If no proper evaluation of the MRF or commingled collection was done, is the rational to build an Incinerator based on similar flawed reasoning?

Food waste still mixed with residual waste

The calorific value (CV) of the waste presently being sent to the continent for burning is 10.5 MegaJoule per kilogramme (MJ/kg). This is the general (residual) waste, from our black bins, minus un-burnable inorganic material that is mechanically removed.

The calorific value of plastics in comparison is 38, paper 18 and wood 20 MJ/kg. If the average is 10.5, what is bringing the CV of the mix down? The obvious answer is the amount of food in the general waste stream.

We all know food waste won’t burn on its own, so it needs plastic, paper and wood to make it burn. If in future plastic bottles are removed from the residual waste due to the deposit scheme and plastic films become biodegradable, for disposal by composting or AD, how will the food waste burn? It will only do so if the amount of food in the waste is reduced. This suggests that the council will have to improve their food waste collections and composts or digests this fraction.

If food waste collection increases, the whole waste disposal system therefore moves from burning to composting or anaerobic digestion. With AD, methane is produced and this can be piped through existing gas pipes to feed those in fuel poverty, with out the expense of the proposed EFW hot water district heating system.

Lost control with bins for flats in the street

A walk down Fonthill Road illustrates how difficult food inclusion is to avoid. Large bins in the street are open for anyone to dump any waste they like. People who live in flats are asked not to do this, but unlike the old kerbside separation system we had for houses, the council staff have no control of what is put into these bins. The council seems to have given up trying to get us to keep food, electrical components, batteries, etc out of our general waste; incineration provides an easy disposal route. A nice shiny incinerator will save us changing our habits, while satisfying the Scottish government’s requirement for zero food waste to landfill by 2020.

Increased recycling rate and reduced landfill

By introducing recycling collections for flats for the first time, the rate of recycling for the town is guaranteed to increase. However, a better system where waste is put out by flat owners must be trialled, if the flat recycling system is to become less contaminated and free from food waste.

The claim that the city is reducing its landfill costs, while true, is ingenuous. Swedish EFW plants don’t accept waste for burning for free; they charge a gate fee. All we have done is to change landfill costs for gate fees. As most of the landfill cost was tax, the government is the loser.

Proposed EFW plant for Aberdeen, the shire and Moray

As the late labour minister Denis Healey once said, “when you are in a hole, stop digging”. We presently have a system for shipping our general waste to Europe for burning, so let’s stick with this for the moment. When the strategy for deposits for bottles is decided, and the future for recyclables becomes less unpredictable, we can then review the export of waste for burning. If biodegradable packing looks like becoming mainstream, then the collection system for biodegradable waste needs to be increased to match the increase in volume.

The collection system for flats must be radically changed to one like houses but with smaller bins. Aberdeen residents must up their recycling rates. If Moray is achieving 59%, why is ours only 39%. Only when the future of waste treatment is clearer, should major investments in incinerators, or probably by then, anaerobic digestion plant be contemplated.

References

| Eunomia, 2014. Residual waste infrastructure review. Issue 7. Pp33. www.eunomia.co.uk |

| Lets recycle, 2017. https://www.letsrecycle.com/news/latest-news/rdf-export-may-become-as-expensive-as-landfill/ |

| Scottish Government, 2011. Zero waste Scotland. http://www.gov.scot/Publications/2011/10/14112444/5 |

| Unilever, 2017. https://www.unilever.com/news/press-releases/2017/Unilever-commits-to-100-percent-recyclable-plastic.html |

| WRAP (2016). Harmonised Recycling Collections Costs Project: Phase One. http://www.wrapcymru.org.uk/sites/files/wrap/Harmonised%20Recycling%20Report%20Nov%202016.pdf |

| ZWS, (2017). The Composition of household waste at the kerbside in 2014 – 15. By Phil Williams. pp 21. |