Travel

Travel

6-01-25

Travel is often a major component of our personal carbon footprint, so there is considerable scope for lifestyle changes to minimise our CO2 emissions. The most obvious one is whether we own or use a car and if so what type.

Table 1 below shows the total carbon emissions for some popular cars. The total is made up of the embedded CO2 required to make the car, divided by its life, and the CO2 emitted over a year’s travel. The cars are assumed to last 13.5 years and be driven 7,500 miles (12,070 km) per year. The VCA emission results are laboratory tests, so are an underestimate of actual fuel and CO2 emissions.

Table 1. Annual CO2 emissions plus embedded CO2, for cars having a 13.5 year life and driving 7,500 miles per year

| Make | Model | Engine size (L) & fuel | Weight

(tonne) |

Annual Embedded CO2

(tonne/an) |

VCA test

CO2 emission (g/km) |

Annual emission

CO2 (tonne/an) |

Total CO2

emissions (tonne/an) |

| Honda | Jazz | 1.3 P | 1.047 | 0.54 | 106 | 1.28 | 1.82 |

| Skoda | Fabia | 1.4 D | 1.186 | 0.61 | 104 | 1.26 | 1.87 |

| Ford | Focus | 1.5 D | 1.328 | 0.68 | 99 | 1.19 | 1.87 |

| Ford | Focus | 1.5 P | 1.328 | 0.68 | 127 | 1.53 | 2.21 |

| Nissan | Qashqai | 1.2 P | 1.318 | 0.68 | 129 | 1.56 | 2.24 |

| BMW | X 3 | 2.0 D | 1.750 | 0.90 | 161 | 1.94 | 2.84 |

| Range Rover | Sport | 3.0 D | 2.115 | 1.090 | 185 | 2.23 | 3.32 |

| BMW | X 6 | 4.4 D | 2.265 | 1.168 | 258 | 3.114 | 4.28 |

NB:Embodied energy 90 GJ/tonne of car, Burning fuel produces 77.4 kg CO2 /GJ energy produced. (http://energyskeptic.com/2015/how-much-energy-does-it-take-to-make-a-car-by-david-fridley-lbl/ and https://www.volker-quaschning.de/)

The message is that smaller cars compared to larger ones emit less CO2 and are therefore more environmental. If one owns a car, it’s footprint per person is reduced if it: –

- Carries more than one person

- Is just used for shopping, day trips, holidays, and snowy days

- Is not used for commuting

Leaving the car at home and walking or cycling to work reduces carbon emissions but you are still responsible for the embedded carbon used to make the car.

Status

In societies present mindset, the status of a car owner increases as its carbon footprint increases. This must change as the risks of climate change becomes more widely recognised.

We are all guilty of unconscious bias towards status. If we hire a consultant at £1000 per day and he turns up in a Honda Jazz, we may wonder if he is going to give us good advice.

Electric cars and hybrids

Electric cars are the future, so within the next 10 years you too may be driving one. The Scottish government aims to phase out new diesel and petrol cars after 2032. Pure battery electric cars (BEVs) have no tailpipe emissions, so do not pollute town air with nitrous oxide emissions as diesel and petrol cars do. The carbon dioxide emissions per km travelled, using electricity from the grid, is about 30 gm/km. This will reduce as renewable energy increases and fossil-fuel based generation to the grid decreases. The lowest emission petrol or diesel cars emit about 100 gm CO2 / km. Fuel costs for electric vehicles are approximately a quarter that for petrol or diesel vehicles.

Types of electric car

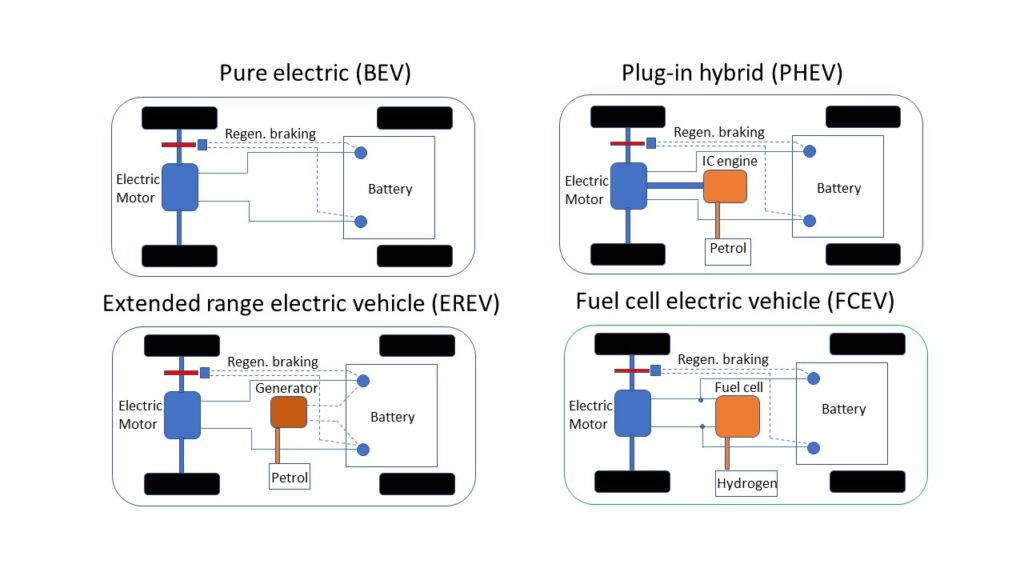

Schematic diagrams of the four types of electric cars are shown in the diagrams below. All have an electric motor driving the wheels and are fitted with regenerative braking (RB). RB acts when you apply the brake but at the same time charges the battery as the car slows down.

The plug-in hybrid electric vehicle (PHEV) has in addition to the electric motor a petrol internal combustion (IC) engine, which can take over from the electric motor if the battery capacity goes below 20%. The fuel tank size determines its maximum range.

For commuters with a relatively short commuting distance and home charger, this vehicle can provide low cost, pollution free motoring for daily use, with long range capability using petrol for trips away and holidays.

A more recent development is a fuel cell hybrid (FCEV). This has an electric motor as a power unit, and either a battery or a fuel cell to provide the electricity. The fuel cell converts compressed liquid hydrogen, stored in a tank, into electricity to power the electric motor and charge the battery. The fuel cell is “solid state” with few moving parts, so should need minimal maintenance.

What type of driving do you do?

Your driving schedule and, if you own one or two cars, is likely to impact on what you buy.

Likely scenarios are: –

- Drive to work daily 10 – 30 miles each way, with car used at weekends for longer journeys

- Long distance journeys of 250 miles, several times per week

- About town as a second car, used for delivering and collecting kids and shopping

Consequences of different power systems

The benefit of the BEV (e.g. Nissen Leaf, Tesla,) arrangement is its simplicity. The disadvantage is that on long journeys you must stop and charge the battery, which may take 30 minutes to charge from 20-80% at a rapid charge point or 13 hours on a home charger overnight. As battery efficiency and associated driving range improves over time, more people will opt for the pure electric BEV.

The plug-in hybrid (PHEV) and extended range hybrids (EREV) in contrast have two power units, which adds complexity, weight and moving parts that wear. However, they can be filled rapidly at a petrol station like a conventional petrol or diesel car, if the battery charge is exhausted.

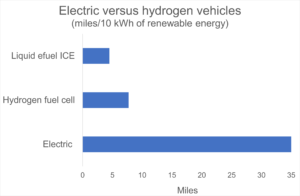

The fuel cell hybrid (FCEV) is still in development and needs liquid hydrogen fuelling points which are few in number. The horizontal bar graph, above right, shows just how inefficient hydrogen powered cars are. The graph shows how far a car will go on 10 kWh of renewable electricity, when supplied to an electric car 1) using a battery, 2) a fuel cell and 3) burning the hydrogen in an internal combustion engine (ICE). Making liquid hydrogen from fossil fuels is an even less efficient process, making the cost of hydrogen eight times that of electricity (See 15 min video on electric-versus-hydrogen cars). However, as the grid is increasingly supplied by renewable energy, hydrogen production may be justified as a way of utilising surplus wind or solar energy. Read eight page review “Hydrogen and CCS assessment” for further background reading.

Charging arrangements

The charging options are: –

- Charge overnight in your own garage, forecourt or Trojan charge point (See photo opposite).

- Charge at a public charging point either free or charged, see below. These will increase in number over time.

- Trailed cable from house or flat across pavement.

For the daily commuter, with a hybrid (PHEV) or extended range EREV, with a short electric range of 30 – 60 mile, overnight charging on your own system is the ideal. If you have pv solar panels on your roof, the use of a Zappi charger will preferentially use solar energy, saving over 40% of your electricity charging costs.

Daily charging at public points requires the driver to plug in the vehicle for up to 30 minutes using a rapid charger, or up to 5 hours if using a fast charger. If charging at some council car parks, you have to purchase a parking ticket, unless you stay with the vehicle during charging or you have a parking permit for that area. NCP car parks always require parking payment. If you live in a flat or have no driveway, a pure electric car (BEV) with a greater electric range will be a better choice. You may only need to charge your car once or twice per week.

Charging at public charging points involves some uncertainties. To ensure the point is available, you need to have on your mobile phone an app like the “Charge place Scotland”. This app identifies all available charging stations, whether they are rapid or fast charge, and most importantly, if they are being used by somebody else. This gives real time information, so that you can choose which charging point is available.

When going on long journeys, the Satnav display on the car will tell you which charging points are in range, so that you can make a strategic decision as to where to stop for a charge. Journeys to remote places need to be planned with care as charging centres can be few.

If you live in a flat or have no drive way, charging in the street may be the only option. The council may allow a cable across the pavement, so long as it is covered with a safety cover . This option is not however a long term solution. If take up of electric vehicles is to include home owners without driveways, councils must urgently address on street charging. With the advent of low powered LED street lighting, cabling to street lights is likely to have sufficient capacity to supply charging sockets for car charging.

Range anxiety with battery only cars

In the past the primary concern of car purchasers contemplating a BEV is “Will I get stranded between charging points?”. The thought of being stuck in snow at night with a flat battery is not pleasant.

The specifications of a sample of electric cars is shown in the GoUltraLow website. Range is increasing every year as battery technology increases, with 150-200 miles now being common. Electric vehicles typically use 0.25 to 0.3 kWh per mile. A Nissen leaf with a 30 kWh battery has a usable capacity of 28 kWh. If the capacity is divided by the use per mile, say 0.3 kWh per mile, its range will be 28/0.3 = 93 miles. Not often mentioned is that battery range reduces by approximately a third in cold weather.

Differences between internal combustion (IC) engine and electric motors

IC engines have many moving parts, which tend to wear out by the time the car has completed 100,000 – 150,000 miles. In contrast, an electric motor’s moving parts consist of just two bearings, which can easily be replaced. Their longevity is therefore considerably greater than IC engines.

In performance, an electric motor has its greatest torque at initial take off. This gives it its initial high acceleration. IC engines need a complicated gearbox to achieve a similar torque at take-off. For lugging power at slow speed, such as towing a boat trailer up a ramp or climbing steep hills, the electric motor gives the best performance. At present, electric cars, unless designed as off road vehicles, are not suitable for fitting tow bars to.

Battery life and cost

The item that worries most people is the battery life and the cost of its replacement. Batteries tend to be under warranty for eight years. This covers both new and second-hand cars. The holding charge decreases slowly over the years. Eventually the battery will need to be replaced.

Low annual mileage car users

Drivers concerned about their carbon footprint often have very efficient diesel or petrol cars doing 40 to 50 mpg, and only do 5 – 6 thousand miles a year. Their car, often bought one year old with 12,000 miles on the clock, maybe cost less than £10,000. It may last 12-13 years before it becomes unreliable. To sell this car in favour of an electric car costing £25,000 to £30,000 does not make financial sense. It may not even make sense environmentally.

For these drivers, the obvious solution is to buy a second-hand electric car. However, their range is likely to be poorer than newer cars and the risk of battery failure more likely. The eight-year warranty normally provided by dealers should provide some guarantee. Since battery life is partly related to battery use, as these drivers are doing so few miles, the risk of battery failure is reduced.

Electric cars second hand can be bought for half price after only 2.5 years. If range is not an issue, reasonable bargains are to be had. Since requirements for repairs increases with age, even in electric cars, a reliable garage or mechanic is required.

Use of hybrids as conventional cars

A recent press release revealed that many hybrid car owners never charge their cars. After several years of use their charging leads are still in their polythene bag. They just fill up at the pumps and the IC engine powers the car. The only beneficial fuel saving is from the use of the electric motor to pull away at lights and regenerative braking when slowing down. If the car is a range extender hybrid, the generator keeps the battery topped up, again with the regenerative braking adding some reduction in carbon emission. Not only is this both a waste of money and failure to capitalise on the potential reduction in CO2 emissions, but it questions why the government should give a grant for buying these hybrids. As a result, grants towards buying these cars have been stopped and only BEVs now get a grant.

Car club cars

For low mileage car users, wishing to go electric, Car Clubs such as Co-wheels, see below, have electric vehicles in their fleet. They have dedicated charging points so charging is not an issue.

Grants, loans a and congestion charges

Since mid-October 2018, the grant for buying a pure electric car has dropped to a maximum of £3,500. Plug-in hybrids now receive no grant. On street charging points can get a 75% grant up to £500. The grant goes to the council to install these.

Pure electric vehicles are exempt from Vehicle Excise Duty and Vehicle Congestion Charges.

Government loans up to £35,000, repayable within six years, are available to buy BEVs. Electric motorcycles can get loans up to £10,000.

Future integration of electric vehicles with the grid

Cars spend 95% of the time parked. If the cars are electric, they can be hooked up to the mains. This then provides an increasingly large battery storage that can be utilised to feed into the grid, when wind and solar power are absent. The concept is known as V2G, or vehicle to grid. Devices would be incorporated in the home’s electrical system to allow the grid to use the energy in the vehicle batteries, with the proviso that the batteries will be charged up again in time for the owner to use the car.

Likely electric vehicle development

Owners of electric vehicles believe that the increasing efficiency of the new batteries being developed will make BEVs the preferred buy. PHEVs and EREVs will as a result become less popular. The car that is causing EV enthusiasts the most excitement at the moment (March 2019) is the Hyundai Kona BEV, costing £30,000 and with a range of 280 miles. For home owners with garages or driveways, with their own power supply, there is little reason now not to buy a BEV. For flats and houses with no driveways, provision of hook ups at lampposts or at on-street charging points is urgently required.

(Source material for electric car section, GoUltraLow website, Energy Savings Trust (EST) website, Office for low emission vehicles (OLEV), On-street residential charge point scheme (ORCS), Specialist Cars, Aberdeen, EV owners Margaret Houlihan, and Ceri Williams, both from Aberdeen and George Jamieson and Douglas Robertson, both of Electric Vehicle Association, Scotland).

Car Clubs

There are several different car share schemes in the UK. The one which operates in Aberdeen is Co-wheels . It is the largest car share company in the UK, with cars in 60 different cities. It is a social enterprise company.

Co-wheels started in Aberdeen in spring 2012, and there are now well over 1000 people using it. The fleet has a total of 34 vehicles available, including two vans. The cars vary in size from a small 4-door to an estate. Eighteen of the vehicles (including the two vans) are electric and five are hybrids. The cars are parked in marked bays on various streets around the City.

How does it work?

- Joining fee £25. A check is made that you have a valid driving licence. Insurance is covered. You will be issued with a smart card which gives you access to the cars.

- There is a minimum fee of £5/month. If you use a car during that month, the £5 is deducted from the cost. So, even if you never use the scheme, it will only cost you £60 for the year.

- Book on line or over the phone. Choose the car you want and the time you want. You can book for any hire time from ½ hour to a week (assuming the car is available).

- The cost is made up of the hire cost and a fuel cost. For the smallest car the hire cost is £4.75 for one hour, rising to £33.25 for 24 hours, and the fuel cost is 18p/mile. There is no fuel charge for electric cars.

- You collect the car directly from its parking bay. Within your booked time, your smart card is recognised by a computer situated on the inside of the front windscreen, and the car will unlock. The car keys are then situated in the front glove compartment and you can just drive away.

Advantages of the scheme

- Economic. You do not have to pay for road tax, insurance, servicing, and MOT, so that your annual car driving will probably cost you hundreds rather than thousands of pounds/year. Also you do not incur the cost of depreciation if you sell your own car.

- No hassle of maintaining, servicing and cleaning your own car.

- Use UK-wide. You can book any Co-wheels car throughout the UK, so that you can travel by train to a distant place (which has Co-wheels cars, of course!) and hire a car while you are there.

- There is a 24-hour phone hotline available if you encounter any problems. This can also be accessed from the on-board computer.

- Reduction of carbon emissions. You will have saved the carbon emissions due to the manufacture of one car solely for your own individual use. You will continue to save carbon emissions as you use public transport, cycling and walking in conjunction with the shared car.

Disadvantages of the scheme

- Pre-planning required. You cannot just jump into a car in your driveway when you want it. You have to book in advance, and perhaps the car you want is not available exactly when you want it. Also you have to collect it from a designated parking bay so you need to go (bus? cycle? walk?) to this place.

- Car not available to drive at booked time. There is the possibility that the previous person hiring the car has not returned it on time, or to the correct parking bay, or that the car keys are not in the glove compartment. By contacting Co-wheels they will do everything they can to sort out this problem.

(Source information. Liz Lindsey, Co-wheels car user and Tony Archer, Aberdeen and Dundee Co-wheels co-ordinator)

Air travel

In considering the carbon footprint of public transport, flying is by far the worst (Table 2). Our interconnected world means that many people who have family in distant parts are torn between looking after the environment and seeing loved ones. To allow them to keep flying, it is beholden for others in business or going holidays, to keep flying to the minimum.

Table 2. Carbon footprint from flying from London to various destinations

| Destination | Distance | Fuel used per passenger (return) | Carbon footprint

(tonne CO2 eq per passenger) |

| (miles) | (kg) | (tonne) | |

| Paris | 212 | 35 | 0.33 |

| Amsterdam | 217 | 36 | 0.34 |

| Dublin | 288 | 48 | 0.45 |

| Prague | 636 | 107 | 1.00 |

| Barcelona | 705 | 119 | 1.11 |

| Oslo | 714 | 120 | 1.12 |

| Rome | 891 | 150 | 1.40 |

| Athens | 1,485 | 250 | 2.34 |

| New York (L Haul) | 3,455 | 414 | 3.86 |

| Sydney (L Haul) | 10,557 | 1,196 | 11.15 |

Source: – www.chooseclimate.org air travel calculator

The air travel calculator (Table 2) gives equivalent carbon footprints, which are 2.7 times the actual CO2 emissions. Emissions of CO2 at altitude have almost three times the global warming effect as emissions at ground level. The lower rate of fuel used per mile on the long-haul flights is because cruising fuel consumption is considerably less than that during take-off.

Whatever way you look at these figures, we should avoid flying if at all possible, especially to distant holiday destinations.

Train and bus

Comparable carbon footprints for public and private transport are shown in table 3.

Table 3. Relative CO2 emissions by public transport and car

| Vehicle | Description | Emissions

(kg CO2 eq/mile) |

Comments |

| Intercity train | 0.15 | ||

| London bus | 0.15 | ||

| Car | Citron , C1 | 0.344 | Driver only |

| Car | Average sized e.g. Ford Focus car | 0.710 | Driver only |

| Air | To Hong Kong | 0.747 + |

Ref: How bad are bananas, Mike Berners-Lee, pp 239, Profile Books. 2010.

+ Assumes extra impact of CO2 emissions at altitude is 1.9 times.

Travelling by rail or bus, or sharing a car, minimise your carbon footprint.

Walking and going by bike rather than car

Using a car weighing between 1,500 to 2,000 kg to transport a 60-90 kg person around town is obviously inefficient and a wasteful use of precious fuel. Use it by all means to transport families or groups on longer trips for days out or holidays, but avoid using it for daily commuting. Walk, bike or take public transport instead. Safe cycling should become a norm.

The lowest carbon footprints are to walk or go by bike. There are no issues with walking other than the journey being too far to walk in the time available.

Cycling in comparison has four issues, safety, effort, road conditions and sweat.

Safe cycling

Safe cycling must be learned. The leaflet Safe cycling in town, gives basic guidance. If you are unhappy about cycling on the road, Google maps show the best ways of going from A to B by bike. These will include cycle lanes where these are available.

Effort

In flat areas, sheltered from wind, effort is minimal. If there are many hills or exposed routes, 21 gears and a lightweight bike are to be recommended. If you become a regular commuter it is simply amazing how quickly your fitness will improve, until you hardly notice hills. If you do find the effort too much, get an electric bike.

Road conditions

In wet or snowy weather, wear clothing that will not matter if it gets grimy. Alternatively take a bus in these conditions.

Sweat

Some people do not like turning up at work all sweaty. If this is an issue, miss your shower at home and have it at work instead.

The joy of cycling

Once you have overcome any apprehension about cycling on roads and are fully fit, cycling really is a joy. Any cobwebs accumulated during a day in the office are dispersed on the way home. Not only can you save the planet but you can enjoy the ride.